Juneteenth History

The second of six Seattle FIFA World Cup 26TM matches this summer will feature the United States Men’s National Team (USMNT) vs Australia on Juneteenth (June 19th). SeattleFWC26 is using this moment of global focus to educate the world on the history, meaning, and impact of Juneteenth. We encourage you to learn more about the history and growth of Juneteenth by visiting and exploring BlackPast.org, the largest online encyclopedia of Black history in America founded by Dr. Quintard Taylor, who passed away in September 2025. With this collaboration to educate, we honor and uplift his life’s work.

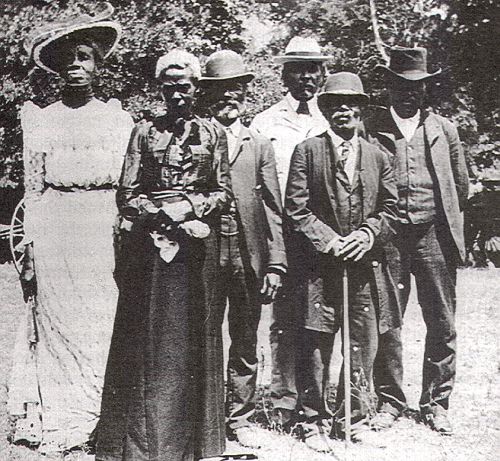

The Growth of an African American Holiday

Any bright high schooler or Constitutional law expert would say that African Americans were formally liberated when the Georgia legislature ratified the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865, guaranteeing its addition to the U.S. Constitution. Yet freedom came in varied ways to the four million enslaved African Americans long before the end of the Civil War. Some fortunate Black women and men were emancipated as early as 1861 when Union forces captured outlying areas of the Confederacy such as the Sea Islands of South Carolina, the Tidewater area of Virginia (Hampton and Norfolk), or when enslaved people escaped from Missouri, Indian Territory, and Arkansas into Kansas. Other Black slaves emancipated themselves by exploiting the disruption of war to run away to freedom, which in some instances was as close as the nearest Union Army camp. President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation liberated all African Americans residing in territory captured from the Confederates after January 1, 1863. These slaves did not have to run for their freedom, they merely had to wait for the arrival of Federal troops.

Emancipation for still more African Americans came in April 1865 when Confederate commander Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to Federal forces at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. With that surrender, the rebellion was over. News of Lee’s surrender spread within days through the former slave states east of the Mississippi River. With that news came the realization by both the former slaves and former slaveowners that freedom would now be the permanent status for African Americans.

Texas, however, was another matter. Isolated from both Union and Confederate forces during the Civil War and thus spared horrific battles on its soil, Texas has become a place of refuge for slaveholders seeking to ensure that their “property” would not hear of freedom. Through April, May, and part of June 1865, they did not.

Finally on June 19, 1865, freedom officially arrived in Texas. One day before, on June 18, Union General Gordon Granger and 2,000 federal troops landed on the beach at Galveston to take control of the last unoccupied Confederate state. The following day on June 19, Granger read the contents of General Order No. 3 from the balcony of Ashton Villa in Galveston. His proclamation announced in part:

“The People of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and property rights between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages.

They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Word of emancipation gradually spread over the vast state despite the efforts of some slaveholders to maintain slavery. African Americans, however, would not be denied the liberty that had eluded them for so long. When the news came entire plantations were deserted. Many Blacks brought from Arkansas, Louisiana, and Missouri during the War returned home while Texas freedpersons headed for Galveston, Austin, Houston, and other cities where Federal troops were stationed.

The freedpeople created a number of poems that reflected their new status including the following:

Slavery chain don broke at last!

Broke at last, broke at last!

Slavery chain don broke at last!

Gonna praise God till I die!

Learn more about the evolution of Juneteenth by visiting this article on BlackPast.org

.png)